In the 80s there was a resurgence in graffiti in New York City and with the help of gallery owners looking for the "next big thing" there emerged a "graffiti movement." Young "taggers" with no formal art training were brought to exhibit in Soho galleries where rich art patrons sipped cocktails and looked at subway car doors covered in swirling, brightly colored patterns and words. The debate raged (and still rages) over whether these were created by artists or criminals and some are even devoted to the study and preservation of graffiti art. Whether you think they are defacements or art, there is no denying they are a continually changing canvas in the urban landscape (here's a New York City graffiti photo gallery from blogger wacky doodler).

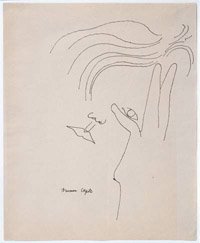

Some fine artists began to incorporate the graffiti aesthetic into their work although they considered themselves outside of the "graffiti movement." Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) was a middle class artist who created works that seem primitive and crude at first glance, yet they contain not only echoes of street art but also of art history: the scribblings of Cy Twombly (1928- ) and Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985). An enigmatic figure who took his outsider status as a young black man and played off of others preconceptions about his background or personality (here's an interesting recollection by a former studio assistant, John Seed) , Basquiat was a master of his image yet careless about his work. He sought to criticize the very people and society that tried to consume his work, so their acceptance only fueled his rejection of them. And in our "celebrity" culture, his early death of an overdose only cemented his reputation. There is still disagreement over whether he was merely a stylist or an artist with a lasting influence and importance.

Some fine artists began to incorporate the graffiti aesthetic into their work although they considered themselves outside of the "graffiti movement." Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) was a middle class artist who created works that seem primitive and crude at first glance, yet they contain not only echoes of street art but also of art history: the scribblings of Cy Twombly (1928- ) and Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985). An enigmatic figure who took his outsider status as a young black man and played off of others preconceptions about his background or personality (here's an interesting recollection by a former studio assistant, John Seed) , Basquiat was a master of his image yet careless about his work. He sought to criticize the very people and society that tried to consume his work, so their acceptance only fueled his rejection of them. And in our "celebrity" culture, his early death of an overdose only cemented his reputation. There is still disagreement over whether he was merely a stylist or an artist with a lasting influence and importance. Keith Haring (1958-1990) was more successful at packaging his street art for mass consumption and he did so willingly. He began his career making chalk drawings on blank advertising panels in the New York subway system. His iconic drawings of glowing babies, barking dogs, television sets, and dancing people were enigmatic, compelling, and even (dare we say?) cute. The random, transitory nature of these subway drawings lent an element of excitement to his work, giving subways riders a vicarious thrill: could they spot the new drawings? would the artist get caught? who was this mysterious scribbler? After much media attention, Haring became a one-man industry, delving into merchandising, public art projects, and his own store "Pop Stop." His breakdancing figures became entwined with the emerging hip-hop culture and tied to the increasingly visible gay rights movement. At the same time, his animations were showing up on "Sesame Street." His art was truly of and for the people.

Keith Haring (1958-1990) was more successful at packaging his street art for mass consumption and he did so willingly. He began his career making chalk drawings on blank advertising panels in the New York subway system. His iconic drawings of glowing babies, barking dogs, television sets, and dancing people were enigmatic, compelling, and even (dare we say?) cute. The random, transitory nature of these subway drawings lent an element of excitement to his work, giving subways riders a vicarious thrill: could they spot the new drawings? would the artist get caught? who was this mysterious scribbler? After much media attention, Haring became a one-man industry, delving into merchandising, public art projects, and his own store "Pop Stop." His breakdancing figures became entwined with the emerging hip-hop culture and tied to the increasingly visible gay rights movement. At the same time, his animations were showing up on "Sesame Street." His art was truly of and for the people.Graffiti has even entered into the realm of conceptual and interactive art. One website gives instructions on making "throwies," small magnetic LEDs. Tossing them on metal buildings or walls lets you make your own illuminated graffiti. Check out the video on the site of a crew in action at night creating amazing street art. Best of all, there's no damage to the building and the "throwies" can be reused until the batteries run out.

The debate may never be settled (for the question "but is it art?" has many answers) but the graffiti artist is sure to remain on the scene, whether underground or mainstream, leaving his mark on the human consciousness.